The Doric World by Gottfried Benn

Gottfried Benn

Contents

I. An Inquiry into the Relationship between Art and Power

II. It Rested on the Bones of Slaves

III. The Gray Column Without a Base

IV. The Birth of Art from Power

V. Art as Progressive Anthropology

Translator’s Note: This is a conservative translation. I felt that trying to reshape Benn’s poetic style would be a crime.

I

An Inquiry into the Relationship between Art and Power

A world in a light that has often been described

To the Cretan millennium, the millennium without war and without man, though with young pages wearing tall pointed collars, and little princes adorned with fantastic headdresses, yet without blood and hunt and without chariots and weapons. To that pre-Iron Age in the valley of Knossos, with its unguarded galleries, illusionistically dissolved walls, delicate artistic manners, colorful faience, Cretan women with long stiff skirts, tight-fitting waists, breastbands, the palaces’ feminine staircases with low, broad steps comfortable for women’s strides —: to these borders, beyond Mycenae, the Doric world.

To the Hittite racial fragments with matriarchy, female rulers, women’s processions, the Aryan man and the bearded gods; to floral still-lifes and stucco reliefs, the great composition and the monumental. This world borders the one that reaches into our movements and upon whose remains our tense, shaken, tragically questioning gazes rest: it is always Being, but wholly captivated; all diversity, but bound; cries in the rocks, Aeschylean grief, yet transformed into verse, shaped into choruses.

There is always an order through which we peer into depth, one that captures life within articulated space, hammers it, seizes it through sculpting, burns it as a bull-procession onto a vase — an order in which the substance of the earth and the spirit of man are still entwined and paired, indeed challenging each other to the highest degree, and through that forged what our eyes, today so destroyed, are seeking: art, the perfected.

If we, looking back at European history, were to choose the formula that it was shaped by peoples who merely extended nature, and those who created a style, then at its inception stands the union of both principles in a people that, coming from the North, stormed the Pelasgian fortresses, toppled the walls, built by the Cyclops, built from stones of such size that, as Pausanias writes, not even the smallest one could have been moved from its place by a yoke of mules. They demolished these walls, shattered the domed tombs, and on poor, irregular, and for the most part infertile ground, began their own stylistic development.

It is the proto-Archaic era. The octagonal-shaped oxhide shields and leather corselets from the early songs of the Iliad give way to round shields and metal armor, beginning of the Iron Age. Rhoikos and Theodoros on Samos discover the technique of casting bronze into molds; a man from Chios learns to soften, harden, and weld it together. The ships grow larger, the entire Mediterranean is navigated; from the fifty-oared vessels of the ancient poems arise galleys with two hundred rowers. Temples are still made of coarse-grained limestone, but around 650 BCE, Melas of Chios produces the first marble statues. The Olympiads begin. The orchestra is added. Gymnasiums become publicly regulated institutions. Music adopts, alongside the Lydian and Hypodorian modes, five new tonal sequences. The kithara, which had previously only four strings, now receives seven. The linen strings of flax and hemp on old instruments are replaced by gut and sinew cords, and fibers from large animals. These developments take place in small states. Argolis is eight to ten miles long and four to five miles wide. Laconia is about the same size. Achaea is a narrow strip of land along the flanks of a mountain that descends into the sea. All of Attica is not even half the size of one of our smallest provinces. The territory of Corinth, Sicyon, and Megara spans barely an hour’s walk. Generally, especially on the islands and in the colonies, the state is nothing more than a city with a port installation or a series of homesteads forming a circle. At the height of its glory, Athens had a circumference of three hours on foot: if one left the starting point of the torch-race in the Academy at nine in the morning, one returned by noon beneath the plane trees, having passed by the Theater of Dionysus, the temples, the Areopagus, both harbors, and walked around the ghostly white grove of the Propylaea.

A world in a light that has often been described. It is morning, the north wind has risen, driving the Athenian boats toward the Cyclades, and the sea, as in Homer, takes on the colors of wine and violets. It laps gently against the rust-colored rocks. Everything is transparent, at least in Attica—everything has color, even the Olympians: Pallas, the white one, and Poseidon, the azure god. Yes, transparent, that is the word. What comes from the Greek hand exists in space, strongly illuminated: plastic, pure object. For centuries it enriched the Peloponnese, filled the hills and islands, settled over the pastures, raising them geographically above sea level, and indeed with something that had gained expression: Lived experience, etched by will and the experiences of the race; porphyry, worked by dream, critique, and highest reason; lay, and upon it the lines of human movement, of its behaviors, its gestures, its spatial composition.

A public, physiological world. People read aloud—that appealed to the functions of ears and larynx. A sentence was a bodily whole: something one could say in a single breath. Reading—this involved the whole organism: the right hand held the closed scroll, the left drew the text columns toward itself, one after the other, slowly, delicately, so that the charta would not tear, the fibers not splinter. The shoulder girdle and arms were always under tension, and one also writes with one's hand. But above all: speech, this corresponded to their constitution! Speech is tied to the moment, tolerates no transmission into the distance. Someone stands here, seeks an effect, is present, asserts, resorts to every means to elevate himself and ruin his opponent, and even, with the listener’s presumed awareness of his injustice, dares rhetorically almost anything. At first there were concrete occasions: courtroom speeches: theft, stolen leather or grain; you had to convince the audience, and that meant its ears, teach them something, make it plausible. Then came speeches for display, for advertisement, speeches for entrance fees. Then came enchantment: symmetrical sentence structure, words of matching tone, nearly rhyming, similarly ending periods. Companies formed, public circles and schools formed to teach style and rhetorical ornament, refinement, mock debates:

“Praise of the Fly” or “Heracles at the Crossroads” or “The Plague”, or “The Fever”, or “The Bedbugs”—and this talent, developed over three centuries, was entirely focused on effect, victory, scorn, laughter, superiority, deepening the sense for structure, deliberate design, and for the playful and beautiful freedom of intellectually advancing forms.

A physiological world: the limbs of the human body are the basis of its measurement: the foot is four handbreadths, the cubit six handbreadths, the finger a quarter handbreadth, the span three times the handbreadth, and so on, up to fathoms and stadia. A stadia is six hundred feet, incidentally the length of a racetrack. The "Attic foot," legally standardized in Athens at the time of Pericles and evident on many buildings, 308 millimeters, then traveled with Philip and Alexander throughout Asia. Its measure of volume is the large jug, which holds the wine and oil, the drink and the ointment, divided twelvefold.

It is morning, its light penetrates the lime-whitened house; the walls are brightly painted, thin, and a thief could break through them. A bed with a few blankets, a chest, a few beautifully painted vases, hanging weapons, a lamp of the simplest kind, everything on ground level, that sufficed for a noble Athenian. He rises early, puts on the sleeveless Doric chiton, fastens the front and back flaps at the shoulders with fibulae; one on the right, one on the left. He does not wear the upper arm bare like the laboring slave. He throws over it the white cloak, drapes it; it is made of thin wool, it is summer. A signet ring on the fourth finger of the left hand, as a seal. It is a land deforested, but rich in bees: honey in the wine, honey in the bread, and sealed wax for closing documents. He goes without hat, without staff. At the door he turns back; the house slave is to put a new wick, made from the woolly leaves of a specific plant, into the socket of the clay lamp, and to bury the amphora, pointed at the bottom, deeper into the earth, it had tipped over during the night.

Now he looks southward. On the shore lie the triremes. They have been hauled up, even the large trans-maritime ones, weighing 260 tons at most. They sailed without compass, sea charts, or lighthouses, hugging the coast and passing among pirates. It is the great merchant fleet of the Mediterranean, which displaced the Phoenicians. the grain-bearing fleet, which won Salamis and Himera. Now he is at the market. On the benches, mostly surrounded by men, heaps of garments, golden chains and bracelets, pins and brooches, wine in skins, apples, pears, flowers and garlands. Above that, fabrics, textiles. The best flax is produced in the plain of Elis, the finest processing takes place in Patras, and there is also colorful silk from the islands. He wants to move on, but must stop; mules are pulling a cart loaded with silver ore from Laureion and with tribute money. Finally the street is clear. It is the one that leads back from Eleusis. How often he saw it during the night of festivals, in the smoke and glow of torches. That is where the potters live, the rustic kind, old school, and they glaze their vases, brown and black on a yellowish ground. The lower parts remain free, only simply adorned, but on neck and shoulders come the straight lines, zigzags, triangles, checkerboard patterns, crosses and swastikas, simple and elaborate meanders. Each adds some local variation, something dialectal, in the development and linkage of ornaments. Soon small, aligned animals appear between the lines, not lions or mythical creatures like in Aegean art, but domestic animals, garden animals, all arranged in bands: hard, clear, assured—the Doric octave. They live on the Piraeus road, at the Dipylon Gate, and on the Sacred Way. Here is the potters’ city.

And there live the purple dealers, who always attract such enormous interest. There lie the shells, with the little white vein at the mouth, from which they release half a drop of juice, white, grim, violet, if one kills them quickly and with a single blow. Those from the rocks are better than those from the sea floor. Trade in purple is still allowed; later it will be forbidden; it will become a color reserved solely for kings and gods.

Outside the city, a theater is being built; that is his destination. A theater: the edge of a hill, into which semicircular rows of steps are hewn; double steps, the front part for sitting, the rear for the feet of the row above, in between stairways: slanted slabs, grooved for grip. Below, in the center, stands the altar. Already finished is the large, smoothly hewn wall meant to reflect back the voice of the actor. The lighting is the sun; the backdrop is the sea, or, further off, the mountains coated in a velvety glow. He casts his gaze over all these things. The theater is no sensation, no feast for the senses and ears. He thinks of that place on the Alpheios, where people were so thirsty, by day in the sun and by night in tents, five sacred days and full moon nights. The river had dried up, its trickle murky. But the Hellanodikai had trained for ten months in Elis; now they were wrestling. The distant cities wrestled with one another. A vast tension, a vast gravity lay over this world of men. And there was no Hellene who, during the struggles and songs, did not again and again let his gaze seek out the table, made of gold and ivory, on which lay the wreaths of victory, and the olive tree between the temples, from which the branches were broken

II

It rested on the bones of slaves

Ancient society rested on the bones of slaves, which they wore down; above them the city blossomed. Above: the white four-horse chariots, the well-shaped ones named after demigods, Victory and Force and Compulsion, and the names of the great sea. Below: the clank of chains. Slaves were the descendants of the indigenous population, taken as prisoners of war, abducted and purchased. They lived in stables, crammed together, many in irons. No one thought about them. Plato and Aristotle regarded them as lower beings, mere facts of life. Strong imports came from Asia. The market was held on the last day of the month. The cadavers stood in a circle for inspection. The price ranged from two to ten minae; that’s one hundred to six hundred marks. The cheapest were the mill slaves and the mine slaves. Demosthenes’ father owned a steel factory, run with slaves. Based on the purchase price above, it operated at a profit margin of twenty-three percent. A bed-frame factory he owned yielded thirty percent. In Athens, the ratio of citizens to slaves was one to four; one hundred thousand Hellenes to four hundred thousand slaves. Corinth had four hundred sixty thousand slaves; Aegina four hundred seventy thousand. They were not allowed to wear long hair. They had no names. They could be gifted, pawned, sold, beaten with sticks, straps, whips, shackled at the feet, caught by neck clamps, branded with hot irons. Slave murder was not prosecuted, at most mildly atoned for through religious rites. They were regularly beaten once a year without cause, made drunk in order to be laughed at, considered utterly dishonorable. If one exceeded the “slave-like” appearance, he was killed, and his owner punished for not having kept him in his place. If there were too many of them, nocturnal murder was unleashed against them, as many as deemed expedient. At a critical moment during the Peloponnesian War, the two thousand strongest and most freedom-hungry were lured out in Sparta by a ruse, and butchered. A great sacrifice of property. There it also belonged to the system of education, from time to time set ambushes along the paths outside the city, where the growing boys had to waylay and kill slaves and helots returning late at night. It was seen as formative, to become accustomed to blood and to have trained one’s hands from an early age. Through this division of labor arose the space for battles and games, for wars and statues, the Greek space.

If one views this space through the eyes of today’s civilization, much of it appears unclear. Themistocles, hero of the Persian Wars, let himself be bribed with thirty talents by the Euboeans, to fight the battle off their island. With five of them, he further bribes one of his subcommanders. After Salamis, he extorts all the islands and cities without the knowledge of his fellow generals. Before Salamis, he is in contact with Xerxes, and after Salamis, the same is true. His servant Sikinnos mediated back and forth for years. In all his actions and speeches, says Herodotus, he acted so as to secure a fallback position with the Persians in case the Athenians did anything to him. Pausanias, commander of the allied fleet, victor of Plataea, regent of Sparta, secretly negotiates with the Persian king during the war to deliver to him Sparta and all of Hellas. Leotychidas, king of Sparta, let himself be bribed by the Aleuads during the 476 campaign and abandoned the favorable war against Thessaly. These are the heroes of the fifth century, two generations before Alcibiades, who would then betray systematically, beautifully, and treacherously.

There: bribery. Here: cruelty and revenge. Panionios of Chios had kidnapped Hermotimos, castrated him, and sold him as a slave. Hermotimos later rose to prominence, became wealthy, visited Panionios and invited him and his sons as guests into his house. There, he ambushed them: first, the father had to castrate his four sons, then the four sons their father, and then he sold them all together. This is reported by Herodotus objectively. The six sons of the king of the Bisalti went to war without their father’s permission. When all six returned safe and sound, Herodotus notes, without further comment, their father tore out their eyes to punish them. That was their reward. From the same pious founder of historiography, we read in another passage about a ruler who committed corpse desecration. We learn of it in passing, in a subordinate clause, as follows: the messengers returned from Delphi, and “Aha!” the ruler cried out, “so that’s what the oracle meant when it told me: ‘Push bread into a cold oven.’” A race full of deception and cunning, in warfare as in ritual. The Phocians dressed six hundred of their bravest men in white: themselves and their shields. They send them by night into the enemy camp with the command to strike down everything that is not white. Total success. Paralyzed with fear, the camp trembled, and they managed to slaughter four thousand. But then: the counter-trick. Their enemies, behind a pass, dig a deep trench, set empty jars into it, covered them with rubble, and leveled it to look like solid ground. The Phocians attacked, fell into the jars, their horses broke their legs, and those rolling on the ground were then easily slaughtered.

Deception at the conquest of Troy; trickery in the theft of Philoctetes’ bow; and cunning too was triumphantly depicted on the east pediment of the temple of Zeus at Olympia. It shows the mythical archetype of the chariot race with four-horse teams: the contest between Oenomaus and Pelops. The king had promised his daughter to the victor, and death to the loser. Pelops triumphs through betrayal: he had bribed the charioteer Myrtilus to replace the king’s axle pins with wax ones. The chariot crashed. When Myrtilus demanded his reward, Pelops drowned him in the sea—but whether betrayal or achievement, it was the victory that counted. Victory erased all. Victory was divine. It was worthy to ascend to the pediment of the highest sanctuary of the Greeks.

There was only one morality: inwardly, the State; outwardly, Victory. The State is the city. It remains the city. Further thought never reached beyond that. Let us consider a specific year in Athens. Inwardly: citizenship is revoked from all whose parents are not both Athenian. Ten percent are struck from the rolls, their property confiscated, to concentrate land and wealth. In short: radical racism. City-based racism. Outwardly: the Delian-Attic League is established. To be clear, among Hellenic states, but it is a League. And Athens holds the power. Now all allied cities must appear before Athenian courts, pay tributes set by Athens. Into suspicious or unreliable cities, Greek cities, allied cities from the Persian Wars, come Athenian garrisons and commanders. Triremes patrol the seas, fleets blockade Hellenic harbors, walls are torn down, weapons confiscated, prisoners branded like barbarians. Neighboring cities, neighboring islands, are annihilated. During the Dionysia, the delegates from the allied cities must pass before the Athenians carrying tablets that display the amount of their tributes. These tributes are presented, in gold and silver, in kind, before the Athenian citizens and their guests. All this, in the "civilized" era of Greek history. But now we immediately stumble onto the countercurrent: during this same procession, all rise to honor the orphans of Athenian citizens who fell in battle, orphans who are clothed and raised at public expense.

Incredibly revealing for the psychology of this upper class is the following incident: after the victory at Salamis, and after the division of spoils, the Hellenes traveled to the Isthmus to award a prize to the Hellene who had most distinguished himself in the war. When the leaders arrived, the votes were distributed among them at the altar of Poseidon, to determine the first and second greatest among them. And each man voted for himself, for each believed himself to be the best. Better than Themistocles, better than Eurybiades, better than Leonidas! And we should also note that during the battle, when their ships passed each other, they insulted one another, belittled each other, accused one another. Out of such rivalries arose their greatest victories.

Just as laws were enacted against harmful predators and snakes, laws should also be made regarding enemies of the state, wrote Democritus. And Protagoras has the father of the gods say: “In my name, enact the law that a man without moral consciousness and without a sense of justice is to be destroyed as a cancerous growth upon the body politic.” Out of this arose the fifth century, the greatest splendor of the white race, its formative, absolute phase, not merely limited to the Mediterranean. Everything revolves around these fifty years after Salamis: the naval battle becomes the axis. Aeschylus fought in it, Euripides was born during it and on the island, Sophocles danced the victory paean among the most beautiful youths. Here is fulfilled the "victory of the Greek": power and art. Here Pericles reaches his height, before the plague and the tyrants arrive. And from both generations, on every document, again and again, two things always break forth, things made to be carried and to be waved: torches and wreaths.

III

The Gray Column Without a BaseBehind this silhouette of Greece, pan-Hellenically blended, stands the gray column without a pedestal, the temple of ashlars, the men’s encampment on the right bank of the Eurotas, its dark choruses —: the Doric world. The Dorians love the mountains. Apollo is their national god, Heracles their first king, Delphi their sacred place. They reject swaddling cloths and bathe their infants in wine. They are the bearers of high antiquity, of the ancient tongue; the Doric dialect was the only one still preserved during the Roman imperial period. Their dream is discipline and eternal youth, godlike being, mighty will, the strongest aristocratic belief in race, concern beyond oneself for the entire lineage. They are the keepers of ancient music, of the old instruments: the kitharode. Timotheus of Miletus had his instrument taken from him because he had increased the number of strings from seven to eleven. He was hanged. Another man had two strings struck from his nine-stringed instrument. With the axe they chopped it down, only the old seven [strings] should remain. “To the fire with the spit-wasting pipe,” cries Pratinas about the flute, because it had, in modern fashion, tried to lead the chorus instead of, as before, submitting to it.

In the temples they hang chains and shackles for their enemies, and they pray to the gods for the entire land of their neighbor. Their kingship is an exercise of power beyond all measure. They may wage war against any land they choose. A hundred selected men alternate in guarding them day and night. Of everything slaughtered, they receive the hide and the back. At meals they are served first, and they receive twice as much as all the others. It is a hereditary monarchy. For nine hundred years the Heraclidae ruled. Even enemies in battle no longer dared to lay hands on them, out of fear and awe of the gods’ vengeance. News of their deaths is carried on horseback throughout the whole Laconian land. In the city, however, women run through the streets and strike on a cauldron. The Doric world, these are the communal meals, to remain ever ready: fifteen men, and each brings something with him: barley flour, cheese, figs, hunting spoils, and no wine. Education is aimed solely at this goal: battle and subjugation. The boys sleep naked on the reeds, which they must tear from the Eurotas with their bare hands, without knives. They eat little and quickly; if they want to add something to the meager rations, they must steal it from homes and farms — for soldiers live off plunder. The land is divided into nine thousand lots; hereditary estates, but without private ownership, inalienable, all equal in size. No money, only iron currency, whose great weight and bulk gave it such little value that a sum of ten minas (six hundred marks, or US$4,550 in 2025 dollars) required a separate chamber for storage and a two-horse cart for transport. All the surrounding states already used silver and gold currency. And even this iron was made unusable: heated until red-hot, then plunged into vinegar, thus softening it. For nine hundred years the royal house ruled, and just as long the same recipes were preserved for cooks and bakers. Foreign travel was prohibited, foreigners were banned from entering the country, and the honoring of the elderly was enshrined. The army during the royal period was exclusively infantry of the elite infantry: hoplites, heavily armored line soldiers armed with thrusting spears. Nine thousand Spartans ruled over a native population ten times that number, and later over the ever-rebellious Messenians. Under penalty of death, one Spartan had to take on ten helots. The whole of society was a camp, a fast-moving army; when shields clashed and helmets threatened from sling stones, that was their march. The number of dead was never disclosed, not even after victories. Woe to those who had “trembled”! Aristodemos, who had “trembled,” the only one to survive the Battle of Thermopylae, later performed deeds of supreme bravery at Plataea, where he fell. And yet he remained despised, for he had “sought death for other reasons.”

Doric is every form of anti-feminism. Doric is the man who locks away the provisions in the house and forbids women from watching the games: any woman who crosses the Alpheios is to be thrown from the cliff. Doric is the love of boys, so that the hero might remain with men, the love of warlike campaigns. Such pairs stood like ramparts and fell together. It was an erotic mysticism: the knight embraced the boy as a husband embraces a wife, and transferred to him his areté, his virtue, mingling him with his own excellence. Doric too was the custom of boy-abduction: the knight abducts the boy from his family. Should the family resist, that is a disgrace, and he takes vengeance for it. But for a boy it is a disgrace not to find a lover, that means he is not called to be a hero. The union takes place at a sacred site; a sacrifice is offered, the knight gifts him with armor and a cup, and up until the boy’s thirtieth year, he is guarded by him and has his legal affairs handled by him. If the ward commits a dishonorable act, the knight is punished, not the boy.

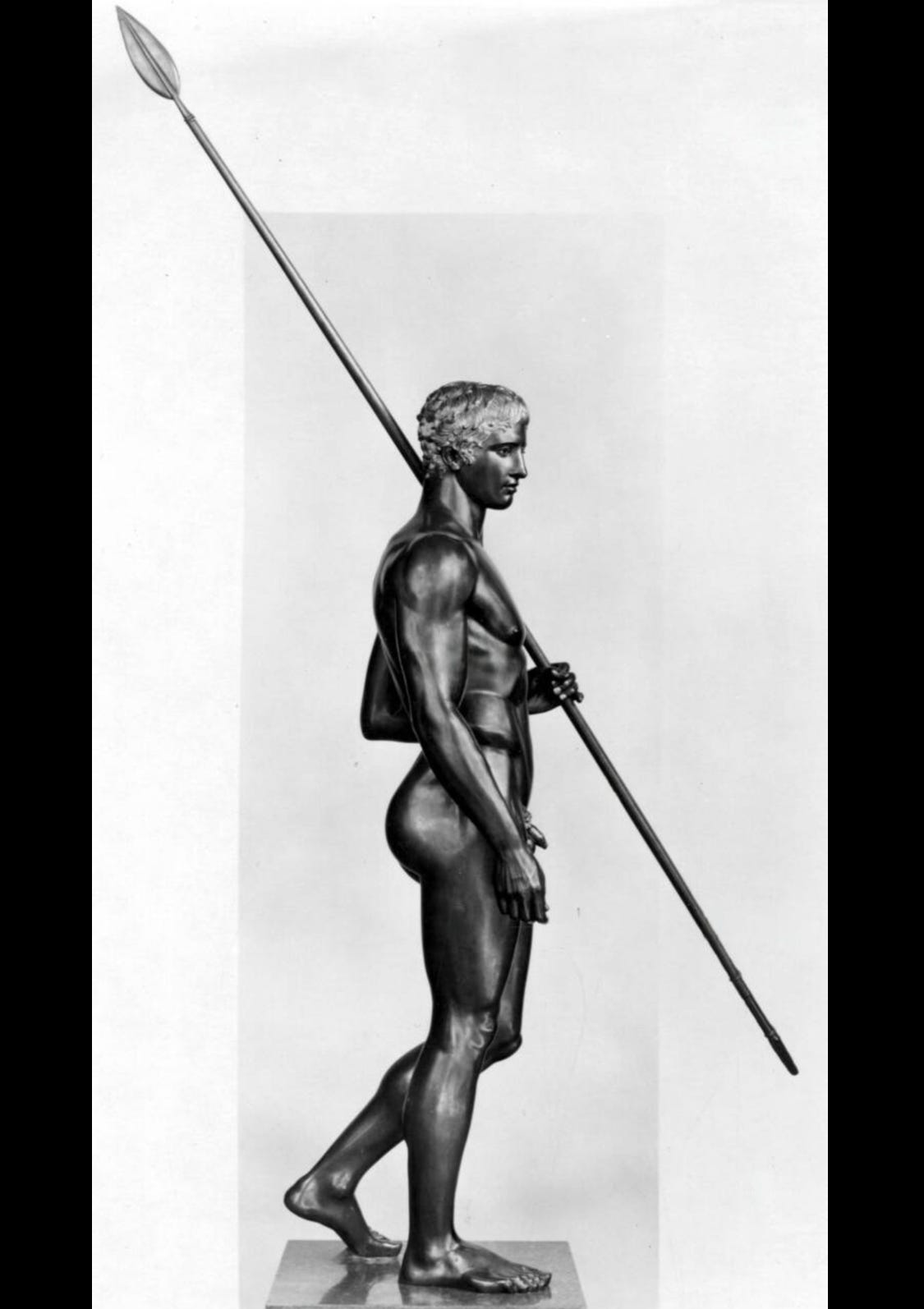

The Dorians work in stone, which remains unpainted. Their figures are naked. Doric art is form, but form in motion, flowing over muscles, male flesh, the body. The body: bronzed by sun, oil, and dust, strigil and cold baths; accustomed to open air, mature, beautifully toned. Every muscle, the kneecap, the tendons at the joints: treated, aligned, worked into each other. The whole shaped by war, yet highly refined. The gymnasiums were the schools where it emerged, and they spread across Greece. Plato, Chrysippus, the poet Timocreon had first been wrestlers. Pythagoras was reputed to have won the prize in boxing. Euripides was crowned at Eleusis as a wrestler. The body proved it: servitude or rank. Agesilaus, the great Spartan, once ordered the captured Persians to be stripped in order to encourage his men. At the sight of their pale, flabby flesh, the Greeks began to laugh and marched forward, filled with contempt for their enemies. Across all of Hellas spread the Doric seed: beautiful bodies. All religious festivals, all great celebrations, were accompanied by contests of beauty. Men chose the handsomest elders to carry the branches at the Panathenaia; in Elis, the most beautiful men were selected to present the votive offerings to the goddess. Large bodies: in Sparta, in the Gymnopidia, the generals and famous men who were not tall enough in stature and external nobility had to march in the secondary ranks, in the procession of the choir. The Lacedaemonians, according to Theophrastus, fined their king Archidamus because he had married a small woman, arguing that she would give him puppet-kings, not true kings. A Persian, a relative of Xerxes, who had been the tallest man in the army and who died in Greece, was worshipped by the local inhabitants like a demigod. Among the wrestlers praised by Pindar were giants: one carried a bull on his shoulder, another stopped a chariot from behind, another threw an eight-pound discus ninety-five feet. Their hometowns inscribed these feats of strength on their statues and monuments to glory. The body was bred: the law determined the age for marriage and selected the most favorable time and conditions for conception. They acted as in breeding stables. A malformed fetus was destroyed. The body was for war, the body was for celebration, the body was for vice, and finally, the body was for art. That was the Doric seed, and the story of Hellenic history.

Doric is the Hellenic concept of fate: life is tragic, yet tempered by proportion. Sophocles is doric in his development: “It is good when mortals do not desire more than what is fitting for man.” Doric is Aeschylus: Prometheus is titanic, he severs himself from the All (Universe) and the Aether with curses and oaths, he steals from the gods, and yet is always the prey of Moira, of fate, of proportion. That which balances captures and forges him. Nowhere does the thread of the Parcae let him go. With Euripides begins the man, Hellenism, humanity. With Euripides begins the crisis, it is the age of decline. Myth is exhausted; the subject becomes life and history. The Doric world was masculine, now becomes erotic; questions of love arise, female themes, female titles: Medea, Helena, Alkestis, Iphigenie, Elektra. This series ends in Nora and Hedda Gabler. Psychology begins. The gods become small and the great become weak. Everything becomes mundane: the mediocrity of George Bernard Shaw. “You have taught babble and glibness of tongue,” says Aeschylus in Aristophanes’ The Frogs, attacking Euripides. “You’ve emptied the wrestling yard, seduced men by tongue-wrung rhetoric into disobedience, even the crew of the ships. When I was still alive, by heaven, all they knew to yell was for hardtack and ‘Ahoi!’ to get to work! But now, thanks to you, Euripides, ‘to carry the torch in the race,’ who is satisfied with that, when physical discipline is in decline?”

The decline of physical discipline — with it sank the Doric world, Olympia, the gray column without a foot, and the oracles favorable to the ruling class. Euripides is skeptical, solitary, and atheistic. In his work, abstract concepts already rise in isolation: “the Good,” “the Right,” “Virtue,” “Education.” He is pacifist and anti-heroic: above all, peace and no Sicilian expedition. He is torn and full of genius, thoroughly pessimistic, undoubtedly daemonic; identical with the greatness and spirit of that deep Hellenic nihilism which began at the end of the Periclean era, the severe crisis before the end of Greekness. Out of the Pentelic marble on the Acropolis, under the chisels of Phidias, in the white glow and polish of classical bloom, arises Pallas, never again equaled, the perfect, the high classical style. But in the now-cosmopolitan bourgeois homes, they keep monkeys. Enormous pheasants and Persian peacocks lure Lacedaemonians to the bird dealers, and instead of mysteries, freemen and metics go to the theater to watch quail fights. The Doric world was the greatest Greek morality, ancient morality, that is, victorious order and power descending from the gods. Their myths speak of no hoards, no treasures, no hollow mountains. Their desire was not for gold, but for sacred things. Magical weapons from the hand of Hephaestus, the Golden Fleece, the necklace of Harmonia, the scepter of Zeus. Sparta was also an inescapable fate. A people distinct from the rest of the Greeks, hardly able to associate with them, mentally very distant. This hardness flared everywhere. Their god of war was depicted in chains, so he would remain loyal to them. Athens expressed the same idea by portraying Nike without wings. The commanders of nearly all Greek armies were indeed Spartans, but a Spartiate fared poorly anywhere he did not appear as a victorious warrior. He was the medieval figure, the "Lycurgian-trained" man, forbidden to question the laws. He was the man from the guardhouse, the fellow gymnast. Hence the phrase: Spartam nactus es, hanc orna. Sparta is your homeland, adorn it, take care of it, you and Sparta are alone in the Greek world.

Let us hear one more story from Herodotus about this Doric virtue, which was so alien and eerie to the Orient, to all of the ancient world: Some defectors, men from Arcadia, came to the Persians at Thermopylae. The Persians brought them before the king and inquired what the Hellenes were doing at that moment. The men answered that they were celebrating the Olympic festival and watching the contests of athletics and chariot races. Then the Persian asked what prize was offered for such a competition. They replied: the victor receives a crown of olive leaves. At that, a Persian nobleman spoke a sentence that the king interpreted as cowardice. For when he heard that the prize for such contests was a wreath and not treasure, he could remain silent no longer and spoke aloud before all: “Woe to you, Mardonius, what kind of men have you led us to fight, who hold their contests not for money but for excellence.” That excellence, that wreath, that festival of competition held between the great battles, that was the Dorian world behind the Panhellenic silhouette.

IV

The Birth of Art from PowerFor a century we have been living in the age of the philosophy of history. If one draws its conclusions, it is nothing more than a feminine reinterpretation of power structures. We have also been living, for some time, in the age of cultural morphology, a stage of high capitalist flourishing, a kind of romanticism meant to finance expeditions to wild peoples. The liberal era was unable to grasp peoples and men — “to grasp,” even the word sounded too violent.; it could not recognize power. Regarding Greece, it taught the following: Sparta was a sorrowful horde of warriors, a caste of soldiers without a cultural mission, a hindrance to Greece, “everything arose in opposition to power.” Modern anthropological theory, however, which is forming itself as a new science, sees precisely in power and in art two sibling forces, the great spontaneous energies of ancient community. Hellenism teaches, in any case, this: sculpture, the art of statues, unfolds at the very same moment as the public institutions through which the perfected human body is shaped. These arise in Sparta. It is the moment when the head still has no cruder designation than the torso and limbs; the face not yet distorted, refined, or worked over. Its lines and surfaces merely complete the other lines and surfaces. Its expression does not seem thoughtful, but motionless, almost extinguished. The general posture and entire movement, thus nature, that is the meaning of the figures; these are statues of pure limbs, they contain scarcely any spiritual element. They are the limbs of the gymnast, the warrior, the wrestler. Such a statue column is solid, its limbs and torso have weight. One can walk around it and the viewer becomes aware of its physical dimensions. They are nude, and here a group comes from bathing or running, also nude, and one compares —: this educates.

It is the moment in which the orchestra, previously an undefined kind of performance at funerals, youth marches, made up of improvised songs, festival songs, revenge songs, merges with gymnastics, the nucleus of competition as well as of lyric-musical poetry. This happens among the Dorians, in Sparta. Here, everything is united: soldierly discipline shapes it, binds it. From here it spreads with the generals to the rest of Greece. The choruses, the statues, but also the music. The Dorians were by nature highly musical, with extraordinarily sensitive ears. They sang freely and moved as they did. Within the people, there existed constant types of melodies, the so-called Nomoi, ancient songs: grinding songs, songs of the weavers, the wool-spinners, the reapers, the nursing women, the field laborers, the grain-pounders, the cattle-herders’ songs. In addition, there were ancient dances: one was called “Corn-winnowing,” one “Shield-lifting,” another “Owl.” Most of the old music, in which words and tones were united in a metrical-methodic union of words and tones, we can no longer fully grasp today, no longer relive. It was a peculiar union of music and gymnastics, of dance and mimetic action, which was called Gymnopaidiai, and which were elevated into panhellenic existence by Thaletas of Sparta during the 28th Olympiad. They were poems for choruses, accompanied by movements, and they became the starting point for higher lyric poetry and for tragedy. And even if we can no longer fully understand the individual elements, it is still deeply meaningful to us that they originated in Sparta. Sparta was called “the most song-rich of the Hellenic cities,” it was unquestionably the musical center. Here, music was first incorporated into the athletic contests as a musischer Agon in 676. Here, the various folk song styles of the individual Doric regions were gathered and organized according to artistic rules. Here, a universal system of tones was established. Beginning in 645, there was even a lawgiver for music. Music was a mandatory subject and had to be practiced by all inhabitants until the age of thirty. Everyone had to learn the flute. Through poetry and song, laws were handed down to descendants. Men marched into battle to the sound of flutes, lyres, and kitharas. “Excellent kithara-playing comes before the sword,” sang Alcman.

And the soldierly city carried this throughout Greece with its armies: Doric harmony, the exalted choral poetry, the dance forms, the architectural style, the strict military order, the complete nudity of the wrestler, and gymnastics elevated into a system. In the ninth century, the movement began to spread. The long-interrupted games were reestablished. From the year 776 onward, Olympia served as an era and a fixed point to which the chain of years was linked. Athletics, music, poetry, stadiums, competitions, and the statues of the victors were not to be separated individually. This was the Spartan mission, and the customs of Lacedaemon gradually displaced those of Homer. Soon there was no city without a gymnasium; it became one of the hallmarks by which one could recognize a Greek city. From such a quadrangle with colonnades and plane-tree avenues, usually located near a spring or a stream, the Academy also arose, and within it, great philosophy was born. In the later Greek period, it was even said that the Spartans had saved declining Greek music three times, and Sparta was depicted allegorically as a woman holding a lyre. It was also in Sparta that the first building was created for musical and dramatic performances: a circular structure with a tent-like roof, in use since the 26th Olympiad during the Karneia festival. Other cities followed later, but this remained the model, even for the next two in Athens: the Odeion and the Theater.

But most significant of all is the Spartan-Apollonian element in sculpture. The art of the statue, first in wood, then in bronze, ivory, and marble, accompanied slowly, step by step and from a distance, the cultivation of the beautiful body. This is the development of the Doric-Hellenic world. At first purely naturalistic, arising from commission and command, it increasingly began to derive its laws from the material itself, from the eternal material, stone. The anatomy of the naked figure, studied in gymnasia and wrestling grounds, had long become the most precise possession of the eye. Now, the inner vision begins to loosen reality from all that is incidental, and from the outline of victors and gods something free emerges. Greekness becomes ever more powerful, ever more heroic, but its history also grows more perilous, “the age of the tragic,” ever deeper, ever more inevitable becomes the shaping of the plastic form. No longer is it merely the eye at work, it is the law, the spirit that now works. Here, a real relationship unfolds, one that historically lasted four hundred years, between public authority and art, from the heroism of external posture and deed, from the battlefields of Marathon and Salamis, to the shaping of the final style of the Parthenon. Here one can truly speak of a birth of art from power; at least in the history of the statue and in this particular context.

This, then, was Sparta the starting point, the germ cell of the Greek spirit. And thus, the earlier mentioned fact is not contradictory: that the Spartan, as an individual, was a stranger in the Greek world. Sparta always remained what it was founded to be: a warrior city, while the other cities had long since become panhellenic, Sicilian, or Asiatic. Constantly demarcating and monitoring borders is one of the mysteries of power, and because Sparta acted accordingly, it succeeded in achieving its final victory and allowing Greece to end in the city where it began. A sense for the greatness of Dorianism runs through all centuries in every political community. A kind of longing for Sparta always remained alive in Greece. “Lakonizontes,” that is, followers and admirers of the Spartan style existed at all times in Athens. In difficult periods, they were repeatedly referred to as “the educator.” And it is quite revealing how Plato, spiritually the last Dorian, who during the era of disintegration once more took up the struggle against individualism, against the melancholy allure of art, the “sweet Muse,” the “art of shadowing,” and for the “Community” and the “reasonable thoughts,” “the moderate life,” the “city with the faultless constitution.” To fight for these, he expresses this longing for Sparta. In the Theages, he speaks of a virtuous man who gives lectures on virtue: “In the wondrous harmony of his actions and his words, one recognizes again the Dorian way, the only one which is truly Greek.” That was five hundred years after Lycurgus. And from this, one can now understand his truly Spartan words against art, those almost incomprehensible words from the mouth of the creator of the extreme idealistic worldview: “When you, O Glaucon, meet the admirers of Homer who claim that this poet formed Hellas, know then: he was indeed the most poetic and the first of all tragic poets, but only that part of poetry which brings forth hymns to the gods and praises of noble men should be allowed into the state.” So speaks this lofty intellectual, great artist, and first bearer of the weighty psychophysical split which would not be bridged for two thousand years. So, speaking beyond all epistemological critique and dialogical-artistic subtleties, from within this deep and transcendent split being, the men’s camp on the right bank of the Eurotas speaks once again, Sparta speaks, Power speaks.

Thus we derive Greece from Sparta, and from the Dorian-Apollonian the Greek world. Dionysus here is again placed within the boundaries in which he stood before 1871 (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music). The Greeks were a primitive people, that is, a people close to rapture. Their worship of Zeus had orgiastic traits. Great, ecstatic waves of emotion surged through them periodically, even in Sparta. They had taken much that was cathartic from the Cretan cults. But in the meantime, we have come to know peoples from travel writings and films, especially negro races, whose existence seemed to be one unbroken series of ecstatic seizures, without any art arising from them. Between ecstasy and art: Sparta must stand, Apollo, the great disciplining force. And since we are no longer so Wagnerianly agitated that we feel the need to trace Tristan back to Thrace, let us look toward Doris, not toward Dion. Let us ask ourselves about the Greek world.

V

Art as Progressive AnthropologyLet us summarize and attempt to arrive at a perspective. We see the diverse empire of the Hellenes, built from individual cities and states. And in each one we see the most unspeakable manifestations of the lust for power: cruelty, bribery, mafia-style intrigue, depravity, savagery, murder, conspiracy, exploitation, extortion.

Among the great figures, we find the most wicked types, like Alcibiades, Lysander, Pausanias; the most horrific, like Clearchus. Liars are honored as saviors of the state, crowned with wreaths and driven to the Prytaneion in chariots, where they are feasted, like Diocleides, who denounced the mutilators of the Herms, only to confess shortly thereafter that he had lied. We see fraud, glossed over: someone failed to notice the mark on the sacks of state funds, and three hundred talents were stolen. We see fraud without disguise: a mere grab into the public coffers. And we see fraud that was publicly legalized, capitalist: “a golden harvest is the speaker’s platform,” that was a saying. The bribing of public orators was thus openly acknowledged. We see corrupt judges: acquittals bought by showing the handles of daggers; buying of court cases. Sycophants (professional and semi-official informers) and counter-sycophants, who “scurry about the Agora like scorpions with raised stingers”; entire generations, entire systems. “I’m a witness in island trials, a sycophant, a digger-up of cases; digging, I’m not made for that, my grandfather already made a living from informing,” says a character in Aristophanes. We see the signs of modern publicity, of the modern state, of modern power.

One cannot say that Antiquity is far away. By no means! Antiquity is very near, fully within us, the cultural cycle is not yet closed. The idealistic system of a present-day philosopher stands closer to Plato than to the worldview of the modern empiricist. Modern relativistic nihilism is, as an emotional posture, entirely identical to what was once called Pyrrhonian skepticism in the third century before Christ. Anaximander’s pessimism, that often quoted sentence: “From where things arise, there they must also perish, according to necessity; for they must pay penance and be judged for their injustice in accordance with the order of time.” This is something Nietzsche ties directly to Schopenhauer in one of his essays. The problem of the “thing-in-itself” arises and remains unresolved to this day. The problem of development begins its history and in our time only grows more confused. Du Bois-Reymond’s Ignorabimus descends from the quoad nihil scitur of sixteenth-century France and becomes the leitmotif of the entire Hellenistic-Roman era. Or let us take the political sphere: the whole vocabulary of governance was already present in the fifth century: “the public good,” “civil equality,” “the party system”; materially, the opposition of rich and common people and aristocracy, between democratic and oligarchic rule, between kingship and popular sovereignty. There were public festivals, national holidays, celebrations for the Hellenes abroad. They spoke of foreign fronts: to the north went the brave and free but barbaric states, to Asia went the cultured but cowardly and enslaved—here, we are fully immersed in our own political principles.

If one views all of this not through moral, sentimental, or historico-philosophical lenses, but according to anthropological principles, we see on one side power, and alongside it, the other great outpouring of the Hellenic people: art. What is the relationship between these two. How did they relate? Let us set aside the fact that many artists left their homelands embittered, hostile, disappointed; those are personal traits. Let us also forget that Phidias supposedly died in prison because he was accused of embezzling ivory. Let us not concern ourselves with the internal crises and catastrophes, the rivalries among individual schools and projects, but instead look at the gradual, centuries-long movement toward the decisive, final, classical style; its emergence during dissolution, and then its end. If we keep that in view, we see that the Dorian spirit, under the protection of its militarism, succeeded in integrating Greek artistic practice into the state and carried its principles across all of Greece, and this contribution of power was immense. But the fact that art was present at all, that it could follow this course of development, was naturally a matter of race, of type, of freely expressing genes. As a whole, it was the tremendous eruption of a new human element. So tremendous, in fact, that one can only describe it as absolute, self-governing, self-contained. It can be seen as something ignited, emerging not from gods, not from any power. One can view them side by side, power and art. And perhaps it is worthwhile for both to be viewed that way: power as the iron clamp that enforces the social process, since without the state, in the natural bellum omnium contra omnes (war of all against all), society cannot take root in any broader sense or beyond the realm of the family (Nietzsche). Or, as Burckhardt put it: “Only on the ground secured by power can cultures of the highest rank rise.” On Sparta, he left us an especially magnificent sentence: “It has never been a gentle process when a new power formed, and Sparta truly became such a power in relation to everything that lived around it. Yet it also managed to impose itself upon the entire educated world, so that it had to take notice of it until the ends of its days, so great is the allure of a mighty resistance, even over millennia, even when no sympathy aids it.”

One could perhaps express it this way: the state, power, purifies the individual, filters his sensitivity, makes him cubic, structured, gives him surface, renders him capable of art. Yes, that is perhaps the expression: the state makes the individual capable of art, but power can never transcend into art. They can share common experiences of mythical, folkloric, or political content, but art remains its own solitary, exalted world. It remains governed by its own laws and expresses nothing but itself. For when we now turn to the essence of Greek art, it becomes clear: the Doric temple expresses nothing. It is not "understandable," and the column is not "natural." They do not reference any concrete political or cultural will within themselves. They are not parallel to anything at all; rather, the whole is a style, meaning that from within, it expresses a particular sense of space, a certain spatial dread (Raumpanik), and from the outside, it consists of specific arrangements and principles to represent it, to express it; thus, to conjure it. This principle of representation no longer arises directly from nature, like politics or power, but from the anthropological principle, which appeared later, only once the natural basis of creation was already in place. One could also say that it achieved conscious awareness as a principle through a new creative act, becoming a human entelechy, after it had already previously worked as a potential and activity shaping the formation and structure of nature. Antiquity, then, is this new turning point, the beginning of that principle becoming a counter-movement, becoming “unnatural,” a counter-movement to pure geology and vegetation, becoming style in a fundamental sense: art, struggle, the embedding of ideal being into material, rigurous study, and finally the dissolution of the material. Solitude of form as an elevation and exaltation of the earth.

It becomes an expression, and in this sense all who have created and interpreted Western culture have embraced antiquity and allowed themselves to be determined by it. Nietzsche in his entirety: the titanic lifting of the heavy, natural blocks of science, morality, conviction, drive, sociology—all these “German illnesses of taste”—into the realms of clarity, of Gaia, into the school of recovery in the most spiritual and most sensual; of national introversion; of the politically “ideological worldview” into the spatial and imperial. One might also say into the domain of power, into the Doric; of religion out of puritanical and passive ideology into the orderly and purely aesthetic. One could also express it geographically: from the Nazarene into his preferred meanings, the Provençal and the Ligurian; the purely race-biological utopia as the late offspring of the declining moral world, into the form-conscious, spiritually shaped, the disciplinary. And with that, form is never understood as exhaustion, dilution, or emptiness in the petty bourgeois German sense, but rather as the enormous human power—power itself—the triumph over bare factuality and civilizational circumstances, namely as the Westerner: the elevation, the real spirit proper to its own category, the reconciliation and the gathering of fragments. Nietzsche said it in a single sentence: “Only as an aesthetic phenomenon is existence and the world eternally justified.” That, however, is Hellenic.

But Goethe must also be seen standing here. His Iphigenia is, factually and politically, absolutely unnatural. That someone sits in Weimar, among court officials and Biedermeier folk, and composes the eminent verses of the Parzenlied, the uncanny invocation of the Tantalids—there is no word to describe this degree of unnaturalness. Nothing grounded points toward it, no current issue reaches into it, no naive causality stands behind it. What works here are distant, inner, elevated laws, those aesthetic laws shaped by antiquity. That these are the ones which ultimately prevail, which shine forth and outlast the times, lies in their central position within the anthropological principle, in their character of bearing weight, of being an axis, the spindle of necessity: Man, that is the race with style. Style is superior to truth; it contains within itself the proof of existence. Truth must be verified, it is an instrument of progress. “Thought is always the offspring of necessity,” says Schiller. We also perceive in him a very conscious shift of the axis from the moral to the aesthetic worldview. He believes the mind is always near utility and the satisfaction of drives, near axes and morning stars—it is nature; but in form it is firmness, it is permanence. Wherever the Tree of Knowledge stands, there is always the Fall into sin, he says, division, transcendence, banishment. Art is the preservation of a people, its definitive inheritance. The extinguishing of all ideological tensions save for one, art and history, this was also recognized by the Romantics. Novalis offers the extraordinary formulation: “Art as the progressive anthropology.”

Ages end with art, and humankind will end with art. First the dinosaurs, the lizards, then the species with art. Hunger and love, that is palaeontology; even insects have every form of domination and division of labor. Here they made gods and art; then art alone. A late world, underpinned by preliminary stages, early forms of existence, everything ripens within it. All things revolve, all concepts and categories change character the moment they are regarded under art, when art poses them, when they pose themselves to it. Man, the hybrid form, the Minotaur, by nature eternally in the labyrinth and, in refined form, cannibalistic, here he is harmoniously pure, monolithic at his peak, twisting creation out of another's hand.

We look back to the Dorian world, to peoples with style; we listen for them, and though they have perished and their time is fulfilled, their generations descend as the sun of the columns, new worlds arise to be illuminated, while on the old only the meadows of asphodel flowers bloom. From the depths, from shards, from masonry, from shell‑covered bronzes, from mud‑fishers, we hear them calling once more.

We also hear from deep beneath the sea‑floor, kidnapped ships sunken there, a law whispered to future generations: the law of the outline, a law that speaks to us most compellingly from the stele of the dying runner at the end of the sixth century, Attic Athens, the Theseion. From his biologically unfeasible movements, movements stylized only in marble, this law speaks to us. It is a law against life, a law only for heroes, only for those who work in marble and cast heads with hammers: “art is greater than nature, and the runner is less than life,” that is to say, all life demands more than mere living, it demands outline, style, abstraction, intensified life, spirit.

“All desire wants eternity,” was said in the previous century. The new century continues: all eternity wants art. Absolute art form. Yet “all that is beautiful is difficult, and whoever nears it must wrestle naked and alone with his own creations.” He too must perish: that is the second Dorian verse. Only laws remain, but these survive epochs. And we remember the great poet of a foreign post‑Greek people, who believed in norms of beauty like the commandments of a god, which preserve the eternal in what has been created. He said the sight of some of the columns of the Acropolis allowed him to sense what might be achievable with the arrangement of sentences, words, vowels in imperishable beauty. In truth, he did not believe that art admits an epilogue.